Somewhere in the rustic foothills of Jamaica, Norma Bell (pictured, photo by Max Blau) longed to leave her parents’ sugarcane farm near the rural village of Catadupa. And eventually she did.

Norma found her way to Montego Bay around age 17. She got a job at a jewelry store. There she met a man named Charles, a Holiday Inn security guard, who asked her on a date. Nine months later, on Dec. 29, 1974, their first son came into the world. To Norma, O’Neil was everything. Charles wanted everything for his family — including a small slice of the American Dream.

Charles moved to Delaware, where he toiled on farms and in factories, and returned home about once a year. In his absence, he mailed presents to O’Neil. One stood out from the rest.

Even today Norma lights up at the thought of 5-year-old O’Neil, clad in a red jumpsuit, running out their front door toward the street with those boxing gloves. This was long before he grew into a force of nature, a champion. She can still picture him, standing atop the light post, posing for passersby like he was on top of the world.

Photo: Eric Buckson coached O’Neil in wrestling at Polytech High School in Delaware. Contributed by Max Blau

3

High-profile debut

The family court judge assigned to O’Neil’s hearing was David Buckson, the former governor of Delaware and father of O’Neil’s wrestling coach.

Look, Eric Buckson told his dad. This kid could be saved. Not long after, O’Neil was back at Polytech and, under his coach’s wing, seized his second chance. He nabbed all-state football honors and won a state wrestling title. His laurels landed him a wrestling scholarship with Delaware State University.

O’Neil commuted from home during college. A true mama’s boy, he always told Norma where he was going on Saturday nights and escorted her to church on Sunday mornings. He also helped look after his siblings. However, O’Neil never got along with Charles, his strict father. The two butted heads in a long string of arguments, ending in a blowout fight in 1995. Neither backed down. O’Neil packed a few bags, hopped on his Suzuki Katana and headed to Georgia, leaving his family and scholarship behind.

He reconnected with an old high-school girlfriend, Ashlei Davis, who had moved to Marietta with her family. He worked for UPS to pay the rent for a place in Roswell and, later, provide for their newborn baby girl. O’Neil watched his first-ever boxing match in person during the 1996 Olympics. He wouldn’t stop talking about the sport as he handled packages during night shifts. One of his coworkers knew of a nearby boxing gym in Doraville. O’Neil jotted down the name and address and decided to visit.

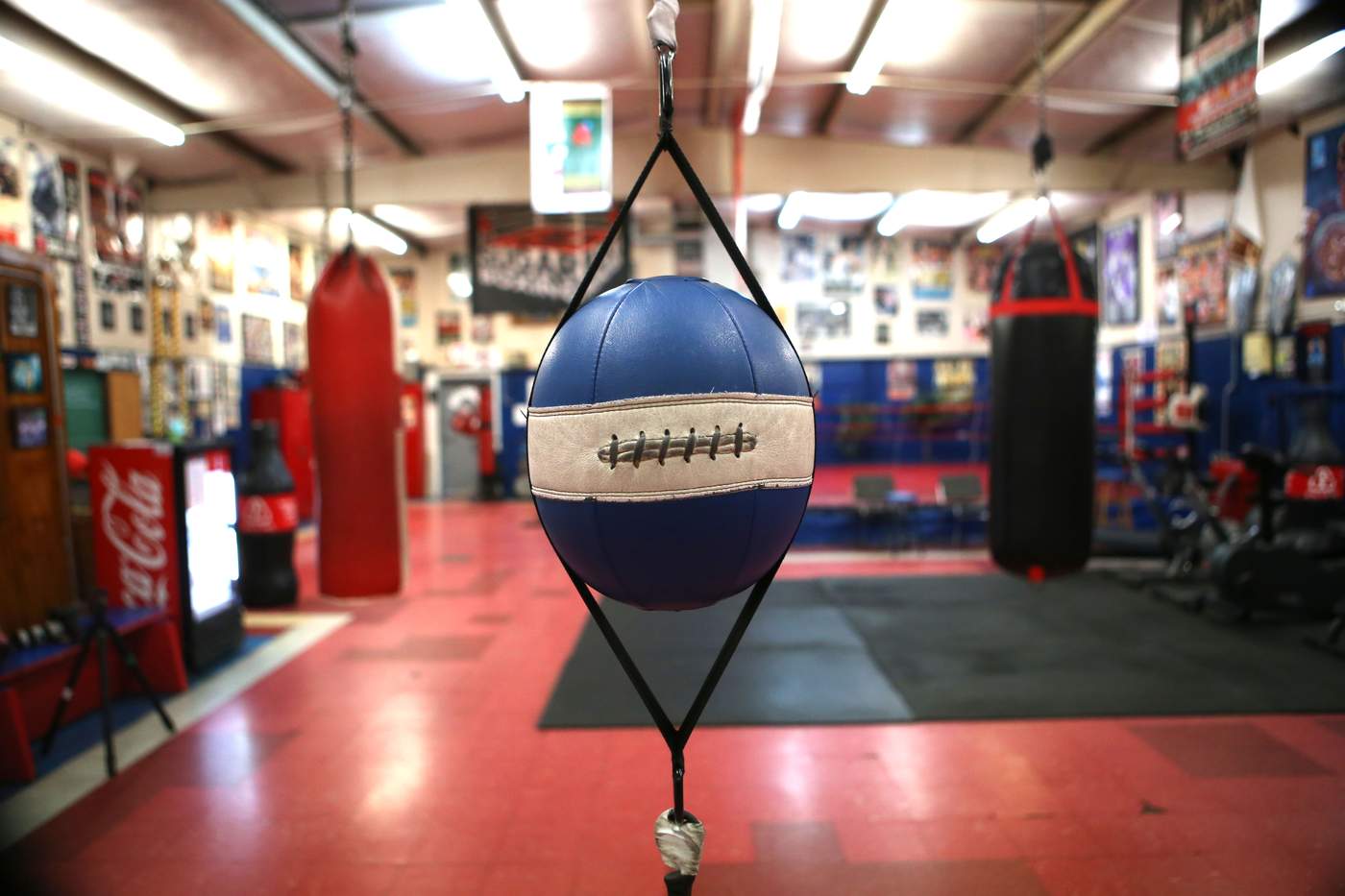

Despite its drab exterior, the Doraville Boxing Club had everything O’Neil needed inside: two boxing rings, punching bags and a wall full of free weights. The posters on the walls seemed the size of boxing legends. Flags of fighters’ homelands draped from the rafters. And the sounds, man those sounds — rapid-fire swoosh of jump rope, the steady rhythm of fists on speed bags, the thumps of gloves echoing off sparring pads — were music to his ears.

O’Neil always seemed to be training: morning laps in the pool, afternoon runs at Stone Mountain and weightlifting sets at night. “Gym rat,” one ex-fighter called him.

Willie Perkins, one of O’Neil’s first trainers, recalls O’Neil bringing his daughter to the gym so he wouldn’t miss a sparring session. The trainer often babysat more than he coached.

“I was willing to do whatever it took to pay the bills and box,” O’Neil told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2001.

O’Neil fought amateur for two years, winning two Golden Gloves, and went pro after only 13 matches. In February 1998, O’Neil “Give ‘Em Hell” Bell made his debut at a black-tie fundraiser inside the Georgia World Congress Center. Stale cigar smoke hung in the air as more than 1,300 people mingled with models, bid on auction items and watched the five-bout spectacle. His light heavyweight fight was third on the card, and his opponent had an instantly recognizable name: Holyfield — Quinton Holyfield, former heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield’s nephew.

Evander sat at a table with his lawyer, Jim Thomas, and fellow boxing legend Joe Frazier. The younger Holyfield, fresh off his debut victory, brimmed with confidence. He landed a hard right punch to start off the fight. O’Neil, weighing a lean 176 pounds, closed his eyes and swung freely. Missed punches soon connected. In a few minutes, down went a dazed Holyfield’s head; up went O’Neil’s arm.

Shocked, Thomas thought to himself: Wow, who is that guy?

Photo: A poster of O’Neil remains as a haunting reminder of his rise to glory at the Paul Murphy Boxing Club. Henry Taylor/henry.taylor@ajc.com

9

Gentle giant returns

Elyun finally received a full psych evaluation during his time served in state prison. According to Chenneil, Elyun was properly diagnosed with bipolar disorder and anxiety, and he received a regimen of treatments including counseling and medication. He told Chenneil his mind felt clearer and he wanted to repair a life that had derailed.

Elyun was released from prison in September 2015. He was 40, living in a halfway house, with the prime years of his fighting life behind him. But he’d started noticing benefits from the treatment he’d long needed.

Man, the medication calms me down, Elyun confided to Jerry Hall during a visit to the halfway house.

Chenneil watched Elyun become a gentle giant again — like he was before boxing — and start making amends with old friends. He lived simply and owned few possessions. He rediscovered his love for cooking. Together they decided he should pursue a restaurant career. Elyun submitted job applications at several restaurants, attended a job fair and chatted with a job outreach program.

He called Norma just about every day.

Two days before Thanksgiving, Elyun and Chenneil got into an argument at her south DeKalb County home over him having one too many drinks.

I don’t want you to be in a space where you can’t regulate yourself, she said.

I’m a grown man, he snapped back.

I just want it to be a safe space, she said.

Elyun decided to return to his apartment off Campbellton Road.

I’ll see you tomorrow, he said.

Chenneil pleaded for him to stay.

Don’t worry, I’m good.

He left around 10 p.m. Elyun called her from the Panola Road bus stop to say the bus had pulled up. As he collapsed in his seat, he cracked a couple jokes and told her goodnight.

After they hung up, Chenneil texted him an old picture of them with the message: Even in the moments when you’re mad at me, or when I’m mad at you, or disappointed, I still love you.

As Chenneil got ready for bed, her phone lit up. She smiled at his response: Love is the thing that matters the most, not the moment.

On a westbound MARTA train, Elyun passed by the Georgia World Congress Center, the place where his career began, on the way to the last stop at the Hamilton E. Holmes station. He made one last call to his ex-wife, who now lived on the West Coast, so he could talk to his 8-year-old son. He then boarded a bus that snaked through southwest Atlanta. A few minutes past midnight, Elyun tugged the cord and hopped off the bus near the Cascade Springs Nature Preserve, a short walk from his apartment.

As he walked south on Harbin Road, three teenagers — Quintavis Robinson, 19; Tycorion Davis, 18; and Cortez Williams, 16 — barreled north in a 2006 Chrysler PT Cruiser. They had started their day by allegedly stealing the car from a Wal-Mart customer before committing robbery in East Point. Just past midnight, they caught sight of Elyun and a man dressed in drag who had also gotten off the bus. According to Atlanta police, the teenagers tried to steal the other man’s purses and shot him once in the hip. Then, police say, they snatched Elyun’s black bag that contained his passport and prescriptions. A single bullet pierced his right shoulder, his heart and both lungs before exiting his body. The teens fled the scene and left Elyun, his white T-shirt and black denim soaked in blood, down in the road for one last count.

Photo: O’Neil with his three championship belts at the height of his career. Contributed

10

Awaiting justice

A hundred family members, friends and associates from Georgia’s boxing community gathered at the Willie A. Watkins Funeral Home to pay respects to the former world champion. His kids were there. So were all the women in his life — Norma, the mothers of his children, and Chenneil. In one corner, there was Pops, his former trainer, who bawled his eyes out. In another, local promoter David Oblas, who gave Elyun’s son a signed pair of his dad’s gloves.

The walls Elyun had erected to keep people at arms-length suddenly crumbled. For the first time, people discussed him — not just the famed boxer O’Neil, but also the human, Elyun. The friends who felt abandoned saw the boxers he inspired. The boxers saw his family, including the daughter he brought ringside so long ago, now a young adult. They slowly pieced together the mysterious decline that beset one of Georgia’s most promising pugilists.

The month after Elyun’s death, Norma was told the Atlanta Police Department had arrested all three suspects. Last year she was pleased to see charges filed, but to date there has been little movement on the case. Dontaye Carter, a spokesperson for the Fulton D.A.’s office, said prosecutors have “actively pursued the case” but declined to comment further regarding a potential trial. For now, the teenagers are still in prison waiting for their day in court, a day Norma and Chenneil hope will bring O’Neil justice.

Following the funeral, Norma flew back to Montego Bay with her son’s casket. She held a second memorial service for her family and had Elyun’s remains cremated. Then she took him back to the foothills of Catadupa to bury his ashes near those of his grandparents. There, Norma hoped her son, who punched his way to minor glory, would finally rest in peace — the ultimate prize after the fight of a lifetime.

ABOUT THE STORY

I initially wanted to know why a champion boxer was slain on a quiet residential road in southwest Atlanta. That search took me from Doraville to Douglasville to Delaware to learn about O’Neil’s life. In the process, I found an untold tale about O’Neil that proved bigger than any sports tragedy. His fight against mental illness – an ugly battle that hurt the ones he loved – had nearly knocked him out. But he clawed back to a life worth living in the months before he died. That story, ugly as it got, needed to be told.

Max Blau

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Max Blau is an award-winning Atlanta-based journalist. He is a Southern correspondent for STAT, the Boston Globe Media’s national health and life sciences website, and has written for CNN, the Guardian and Atlanta magazine. His stories often focus on health care, mental illness and addiction.

Read more stories of athletic glory and the power of the competitive spirit :

Guts and glory

Cerebral palsy is no barrier to the athletic aspirations of Atlanta's Devon Berry

Rock bottom

Ulysses Elijah's road to redemption began with a life-altering fall

The ref

72-year-old lacrosse crew chief Louie Diaz

reluctantly eyes retirement from the sport he loves.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.