Outside the center for unwed mothers, Alan Horne – a black, 6-foot-2, 200-plus pound former offensive lineman on his high school football team — waited in the dark. The weather was typical for late March in Paterson, N.J. — cold with no sight of spring. And the hour was late.

Antonette, the product of a traditional Italian family whom everyone called Toni, was in her third trimester as she sneaked out the window and climbed into the car with the father of her unborn child.

With his barefoot girlfriend at his side, no plan at hand and very little money, Alan drove them to his older sister Darlene’s apartment nearby.

Where the hell you two going? she blurted.

Alan paced the apartment. He didn’t know what the cops might do if they caught him with Toni, but he was more frightened by the thought of losing his unborn son to adoption.

It was 1969, and Alan and Toni were teenagers set to become parents in a time when society forbade their union. Her family had made it clear she was not going to be the mother of a black kid.

While the two juggled ideas for their next step, Darlene cooked — she was good for fixing folks quick meals.

An hour passed and the young couple realized there was nothing to do but return Toni to the center. They had no other options so they convinced themselves her parents would come to their senses and everything would work itself out.

It didn’t.

3

Saying goodbye

Whenever my brothers and I are together, we’re either arguing, laughing or working on a project.

But on this day, we were crying.

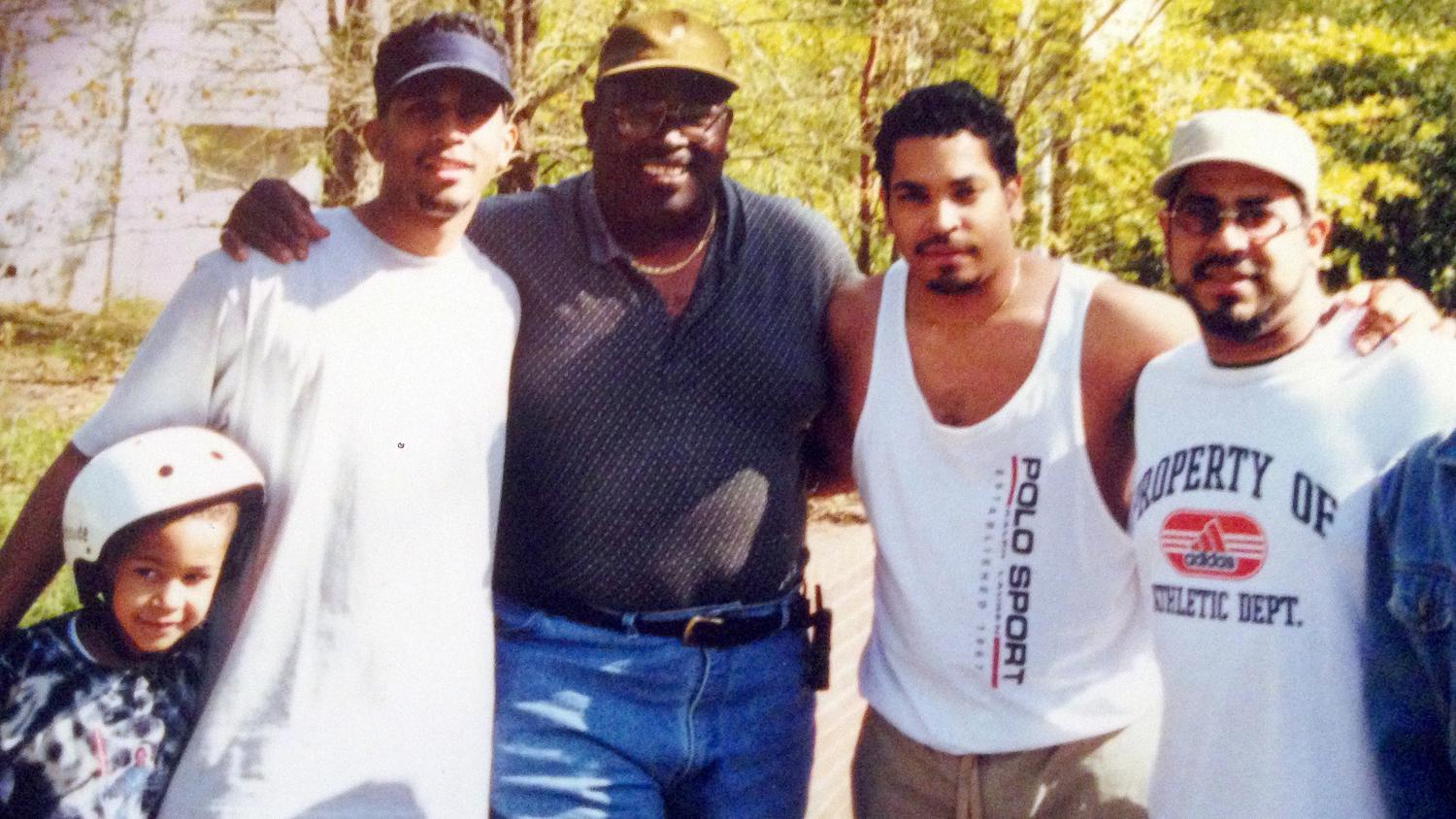

The sun seemed to shine a little harder on the day of Dad’s funeral. There were about 25 of us waiting outside the home he shared with our stepmother, Linda.

The limo driver was late, but no one seemed eager to get to the Thirty-fourth Street Church of God, where the funeral was being held and where Dad had led the men’s ministry for several years.

He’d always served others one way or another. Before he died, he was a counselor at a center for teenage addicts and had recently earned his bachelor’s degree at age 64 so he could teach. He also spent countless hours at the bedsides of elders who were ill. The night he died he was in Baltimore, where he’d gone to visit his godmother in a hospice.

Dad had been the patriarch of the family, and it was evident Tyson was prepared to take on the role now that Dad was gone. He was antsy, pacing around the house and checking on everyone, as if this was his first big test as the family’s new leader. He’d always taken the “big brother” thing a little too seriously.

Byron kept to himself as we prepared to leave the house, occasionally raising a small camera to record the action. “You better not turn that camera on when we get to the church,” an aunt warned him. It was the kind of threat we were accustomed to as kids, and it was usually followed by a swift swat upside our heads.

Dad wouldn’t have minded us documenting the day of his funeral. In fact, he was always a little zealous about our achievements.

At the 2011 Atlanta Film Festival, my brothers and I premiered our first feature documentary, “The Start of Dreams,” about kids using acting as a way to learn with Broadway director Kenny Leon. Mayor Kasim Reed introduced the film to a packed crowd, including comedian Chris Tucker and actress Jasmine Guy. Dad was there too, sitting next to his wife, Linda, and his first wife, our mother Monica. As lovely as the ladies were, it was my dad who stood out, thanks to the bright red suit he wore for the occasion.

We’ve often joked since then about how Dad showed up at our first red carpet event wearing the red carpet.

The limo finally arrived to take us to the funeral. Byron turned on his camera as the family formed a circle in the driveway and Tyson said a prayer before we headed to the church.

After the funeral, we returned to the house and the three of us sat on the back porch where we used to hang out as kids. It was hard to believe Dad wasn’t there with us grilling his famous garlic burgers.

“We need to find a way to honor Dad,” Byron said as he gazed at the funeral program with our father’s picture on the cover.

I knew how.

“Let’s find our brother.”

4

A dead end

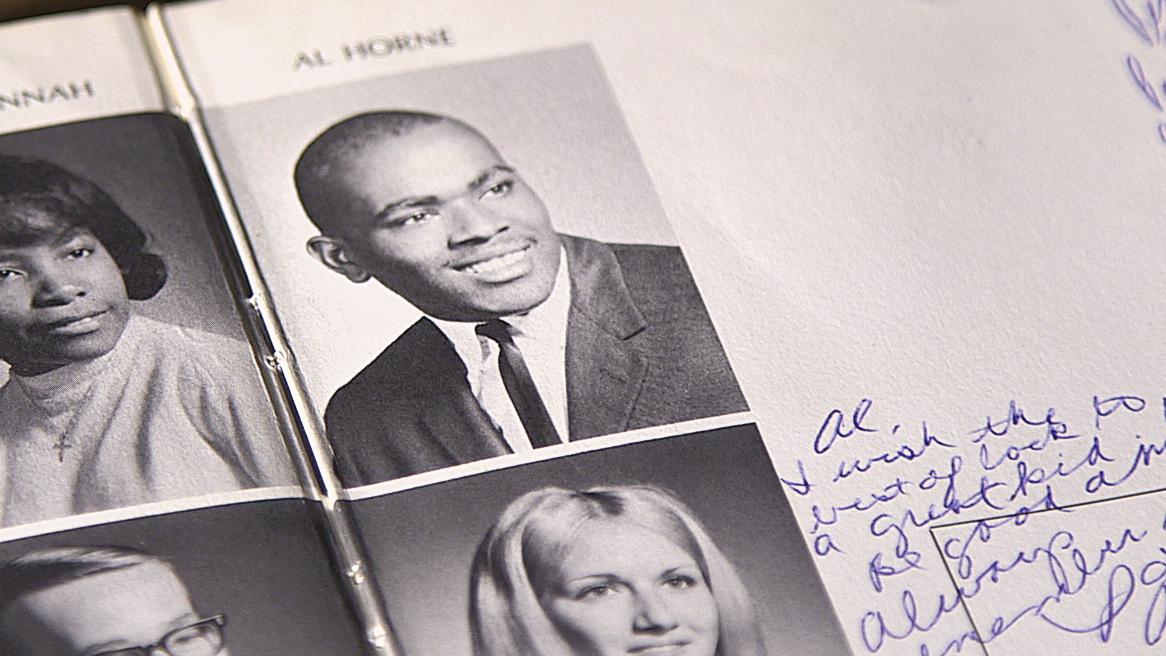

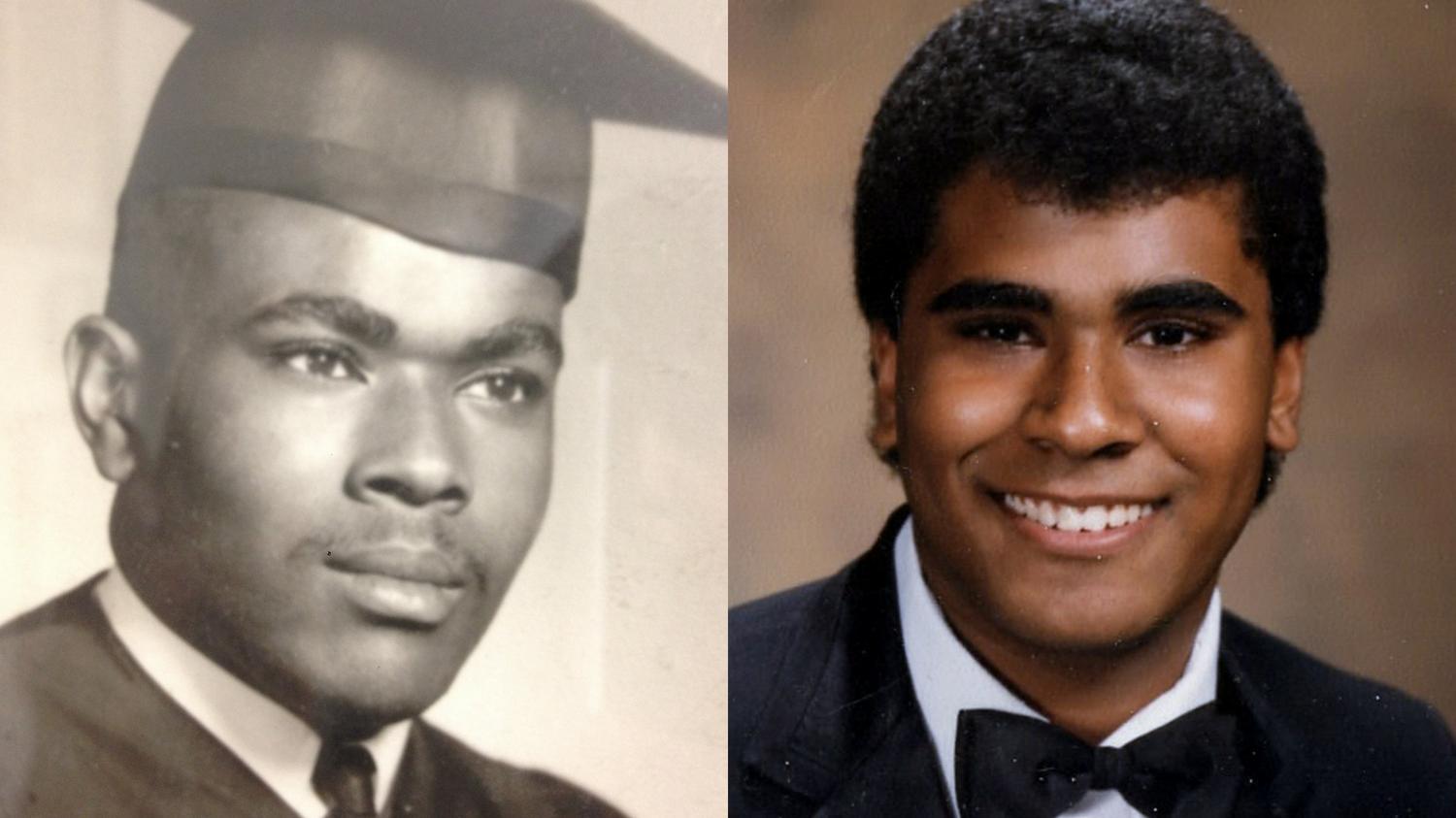

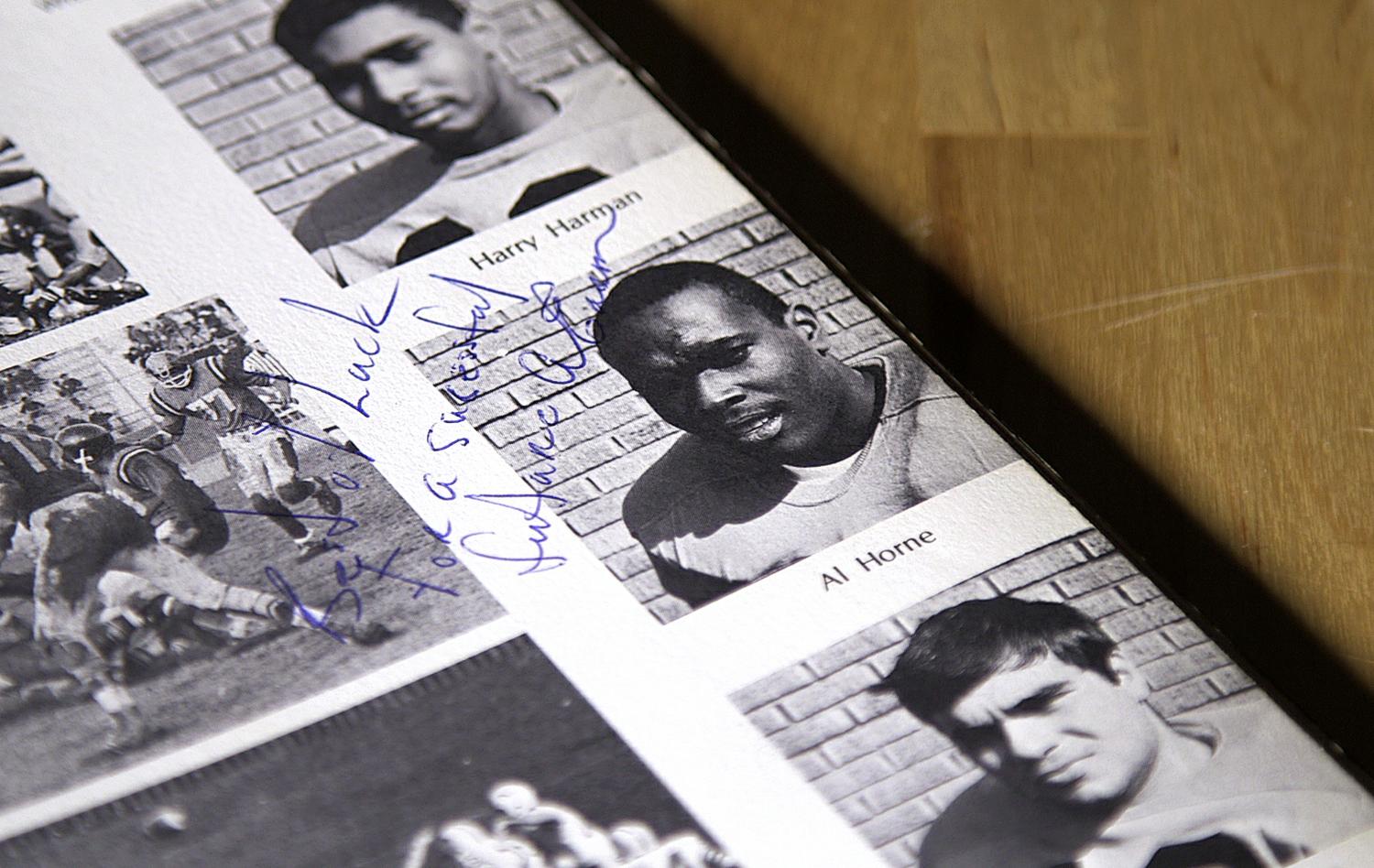

We started by searching Dad’s home office and reading his journals in which he recounted the highs and lows of his childhood. When he was 5, his parents lost everything in a house fire. They moved to the Alabama Projects in Paterson and soon after, his father left his mother with three kids. She had to work three jobs to take care of the family. While attending Eastside High School — the same school featured in the Hollywood film “Lean on Me” — he met Toni, and they dated for over a year.

“That’s when my first son John Alan Savistino was born and I never got to see him,” he wrote.

It’s a simple statement for such a devastating event. The absence of details seemed to speak to his stoic nature, but it was clear there was void in his life and now it had been passed on to his boys.

Our logic was that if we could find Toni, we would find our brother. Byron signed up on high-school, ancestry and genealogy websites, and he plugged in different variations on the spelling of Toni’s and John Alan’s names. Before long, her name popped up and he traced it to her daughter’s Facebook page that contained a photo of the two women together. He sent it to our aunts for identification and they both agreed it was Toni. From there he tracked down her phone number.

I felt a lump in my throat as I dialed the number. I didn’t know what I would say. How do you ask a person whether or not she’s the mother of my brother? Sounds ridiculous.

A woman answered the phone and, fumbling over my words, I began my pitch that ended with: “Did you happen to know or have a relationship with Alan Horne in the late ’60s in Paterson, N.J.?”

“No, I’m sorry I don’t know Alan Horne,” she said and hung up the phone.

I suspected she was lying and had closed that door forever.

5

‘I lost my son’

According to Aunt Darlene, Toni’s parents were a traditional Italian family. They were hard working and kept to themselves. When Toni got pregnant, her parents were determined to keep the couple apart and put the baby up for adoption.

Before Toni started showing, her parents put her in a home for unwed mothers south of Paterson. Darlene said Toni would escape any chance she could, sneaking out late at night, climbing out of windows.

When she gave birth, Dad wasn’t allowed to see her or the baby. He went to the adoption agency and petitioned for custody. His mother was unable to take the child because she was hospitalized at the time, so Dad asked Darlene for help.

She signed papers agreeing to take the baby. She worked as a flight attendant for Eastern Air Lines, had a stable home and she was family. But because she was single, she was denied custody.

Still, Dad continued to fight for his son. The agency told him to get a job to prove he was capable of providing for a child and to come back in a year. So he quit college and went to work at the city gas company. A year passed and Dad returned to the agency to claim his son, but he was told his child already had been adopted. It was too late.

Dad showed up at Aunt Darlene’s doorstep sobbing uncontrollably that day.

I lost my son, he’s gone, he wailed. I’m never going see him.

He was never the same after that, Aunt Darlene said. He wasn’t the optimistic, happy guy everyone knew him to be. This was the early ’70s, and the country’s racial tensions were still simmering. Dad felt he was denied the right to be a parent because he was black. It didn’t stop him from being attracted to white women, though. He soon met our mother, Monica, and created three more boys, Tyson, Byron and myself.

He wasn’t a father without flaw, however. Show me one who is.

My parents separated when I was 6 years old and divorced five years later. For a long time I resented Dad for leaving our mother to raise us by herself, something he resented his own father for doing. After the divorce I only saw Dad during summer breaks, and we barely spoke throughout the rest of the year.

Every time I asked him for help, it seemed to me he had an excuse for why he couldn’t deliver.

Things eventually changed, thanks to my wife Latrisha. As a young couple she and I went through a pretty rough patch, and she asked my dad to intervene.

Ryon, don’t make the mistakes me and your mother made. Take care of your family, he said to me.

I learned then that I needed my father more as a grown man than I had as a kid.

That Christmas night when I talked to Dad about his first son, I asked if losing that child had affected his relationship with my brothers and me.

“I believe it did,” he said. “I was too young to handle something that traumatic and didn’t rely on the one thing that could have gotten me through it — God.”

But later in life he worked hard to be there for us. His devotion to his 10 grandchildren was his way of righting wrongs.

6

I found him

The first anniversary of Dad’s death was approaching, and I was on Facebook practicing my monthly ritual of looking at old pictures of him and reading old posts. That’s when I came across a group page for his high school class. On it was a post about Dad with nearly 40 comments describing how great a football player he was, how nice he was, how handsome.

I joined the page thinking someone might have information about Toni. Five minutes later, page administrator Linda Cantanzariti accepted my friend request and I began quizzing her about Dad.

“Big Al was one of the good guys,” Linda wrote. “(He) always had a huge smile on his face.”

I asked about Toni.

“I remember her well,” Linda wrote. “Toni’s real name was Antonette Savastano.”

My heart started beating faster and my hands shook a little as I tried to find the keys to type my next question.

“So I’m sure you know why I asked specifically about her.”

“Yes, indeed I do,” Linda replied.

We continued our Facebook conversation for three hours that night. As it turned out, Linda was a genealogist who helped connect adoptees with their birth parents. She offered to dig around in the morning to see if she could track down Toni or the child.

Although it was midnight, I couldn’t sleep. For so long we had been searching for “Savistino.” Either Dad had the wrong name, or we misinterpreted his handwriting. I finally had the correct spelling of Toni’s last name and wanted to see what I could find.

Google Search: John Alan SAVASTANO.

I nearly fell out of my seat when I saw the first link: a 2005 post on ancestry.com by the user Kathleen Hammel.

“Looking for information regarding birth parents of Alan John Savastano born July 10, 1969 Paterson, NJ.”

I’d found him.

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Ryon Horne is an award-winning filmmaker and video journalist. He joined The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 15 years ago and has been the company’s video and audio producer for eight years, covering breaking news, entertainment, sports and features.

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

Ryon Horne is one of the many people who work behind the scenes on Personal Journeys each week. He often mans the camera or edits footage for the videos that accompany the feature every Sunday. When he approached me with an idea for his own Personal Journey, he was still in the middle of it and didn’t yet know how it would end. But as a dedicated journalist and filmmaker, he knew a good story when he saw it and he was dedicated to telling it, no matter the conclusion. The result is a moving story about family and brotherly love that transcends all odds.

Suzanne Van Atten

Personal journeys editor

personaljourneys@ajc.com

Personal Journeys Writing Contest

Share your Personal Journey with the AJC and win $750. Everyone has a story to tell. Here’s your chance to tell yours. Watch for details coming June 14.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.