Just two years apart in age, Paula and Vicki Ashmore were as close as two little sisters could be.

Growing up in a tiny brick bungalow near Agnes Scott College in the late 1950s, they shared a makeshift bedroom in the attic where they loved to play school. They would push their twin beds to one side of the room and turn the center of the space into a classroom, complete with chalkboard, square wooden table and two chairs.

Vicki, a girl with a freckled, heart-shaped face and aquamarine eyes, was always the teacher, even at just 6 years old. She would instruct shy little Paula, then a preschooler, to write the letters of the alphabet on the chalkboard and nod encouragingly.

Whether she was playing school or orchestrating a talent show with kids in her Decatur neighborhood, Vicki always took charge, and Paula was her faithful follower.

When they moved in 1966 to a larger house in South DeKalb, Vicki and Paula each had their own bedrooms across the hall from each other. But most nights Paula ended up in Vicki’s room. Side-by-side in a double bed, Vicki would read aloud — “Little Women,” “The Hobbit,” Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” — her voice animated with emotion.

Sometimes they listened to a transistor radio before dozing off. Vicki would pull out the antenna and place the radio between their two pillows. Even though the sound was tinny, Vicki would point out her favorite songs by the Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, the Supremes.

Taken in 1969, this photo captures the Ashmores’ last Christmas together. Vicki is back row right, Paula is middle row left. With them are dad Lynn, mom Gina, brother Jon and little sister Jeannie.

After the move, their father, Lynn, and mother, Gina, argued often, squabbling about money and their father’s drinking. At the first hint of shouting, Paula would scurry into her big sister’s room, and Vicki would soothe her by spinning tales about their lives when they were grown up and on their own.

You won’t always have to hear arguing, Vicki would say. You’ll have your own apartment someday with a white Persian cat and lots of books. You’ll have a cute boyfriend, cute clothes and a stereo to listen to music.

3

A tragic accident

One warm, cloudless day in August, Paula strolled into her backyard to feed her pet rabbit, Tater Tot. Lugging the bag of feed to the wooden hutch, her mind drifted with happy thoughts: Just three more weeks.

Three more weeks, and Vicki would be home.

Three more weeks, and Paula would get to see her sister’s blue-eyed, freckled face. She’d get to hear about Vicki’s host family, the food, the music, everyday life in a far-off land. Would she bring back souvenirs, Paula wondered? Maybe books in Spanish?

Some of the items from the home of Vicki's host family in Peru, include her Spanish-English dictionary, which Paula then used. Photo: Bob Andres, bandres@ajc.com

Her daydreams were interrupted when she looked up from her chores to see her brother, Jon, rushing toward her. The words he shouted made no sense.

Vicki was in a plane crash!

The bag of rabbit food fell from Paula’s hands.

That’s crazy! she shouted.

Furious that her brother would make up such an awful lie, Paula marched into the house. Mama would straighten this out. But as she took her first steps inside, she recoiled at the sound of her mother sobbing.

Standing in her bedroom, hunched over and struggling to catch her breath, Paula’s mother shrieked in a strangled voice.

No! No! No!

A radio on the bedside table affirmed the worst:

There was a plane crash in the Peruvian Andes with American students ...

Photo: The LANSA airlines plane carrying 49 American exchange students crashed in the Andes on Aug. 9, 1970. Following another crash a little over a year later, the Peruvian airline ceased operations.

4

'The best we have'

They were club presidents, choir members, scholars, star athletes. They ranged in age from 14 to 18. Most of them hailed from New York. Just two were from metro Atlanta: Vicki and Joetta Marie Burkett, fellow classmates at Walker High School in DeKalb County (the school is now McNair).

Joetta loved music and wanted to be a doctor someday. She worked part time as a waitress to help cover the costs of going to Peru. While Vicki and Joetta didn’t know each other well before the trip, photographs of them together in Peru, including one snapped at the Cuzco airport, suggested they grew close.

Shortly after takeoff, the pilot of the Lockheed Electra propjet of LANSA Airlines radioed the Cuzco airport to say he was returning to Cuzco.

At some point during the takeoff or initial climb, one of the plane’s four engines had caught fire.

As the plane turned around, it lost altitude and smashed into a mountain, bursting into flames. There were 100 people aboard, including the 49 American students. Two farm workers were killed on the ground. The sole survivor, the 26-year-old co-pilot, was found in the wreckage, badly burned.

Bodies and wreckage were scattered for 600 yards. Many of the students’ bodies were clad in brightly colored ponchos, likely mementos purchased at Machu Picchu. Peruvian potato farmers gathered the bodies from the rocky hillsides. A Peruvian government investigation concluded the accident was likely caused by several factors, including poor maintenance of the plane and mishandling of the engine failure.

On the CBS Evening News on Aug. 10, 1970, Walter Cronkite described the American students as “the best we have.”

“These 49 young Americans did not make trouble. They held a curiosity for a world,” he said.

Paula and her family waited 24 hours before they received confirmation that Vicki’s name was on the passenger list.

A few days later, Maria identified Vicki’s body and her remains were returned to Georgia. The viewings for Vicki and Joetta were held in side-by-side rooms at a Decatur funeral home. They were buried on the same day in August.

Photo: Paula Ashmore has been on a long search to learn more about her sister’s last days on earth. The 57-year-old Dacula resident worried time was running out until one day last August when she discovered a 1971 school calendar from Peru. Bob Andres, bandres@ajc.com.

5

‘A sad, sad household’

Reeling from the loss, Paula sought solace by moving into Vicki’s room. She slept in Vicki’s bed, wrapping herself in her sister’s pastel floral bedspread. Sometimes she would step inside Vicki’s closet and clutch the clothes on the hangers, breathing in her sister’s talcum powder scent.

“I felt like I was in a boat without a paddle or compass,” recalled Paula, 57, who works as a communications manager in the Gwinnett Tax Commissioner’s Office and lives in Dacula. “I lost the person who gave me direction.”

A few weeks after the crash, Paula and her family received a package in the mail from the Alcantaras containing gifts Vicki had collected during her stay — two alpaca ponchos, an Incan pin for her mother, a hemp purse with bamboo handles for Paula. The family also sent other items Vicki left at the house — clothes, Peruvian 45 rpm records and a Spanish-English dictionary.

“It gave us insight into what she did in Peru,” Paula said. “All of the things seemed foreign and exotic.”

In those days, there were no grief counselors at school. There was no mention of therapy to help the family cope with their pain. Paula’s parents’ arguments grew more frequent. Their father lost his factory job and struggled to stay employed. Long teetering on the verge of alcoholism, he became a full-fledged addict. He would later die of a massive stroke at the age of 55.

Paula’s little sister, Jeannie, was only 4 when Vicki died. She was deeply confused and couldn’t fully grasp what happened, but over time she realized Vicki’s death had crushed the family in such a way that no one would ever fully recover.

“It was just such a sad, sad household,” said Jeannie Manning, 49, who lives in Seattle.

For a while Paula used Vicki’s Spanish-English dictionary to write letters to Maria and her family, but they gradually lost touch.

Nevertheless, a pull toward the Spanish language took hold. She studied Spanish at Valdosta State College (now University) and traveled to Mexico and Spain. She got a job as a translator at Coca-Cola and then later as an interpreter at Gwinnett Medical Center.

“I embraced Spanish because I loved Vicki and she chose it,” Paula said. “It was something she loved, and I felt like her way was the best way, and everything she did had to be good and right.”

In other ways, though, Paula did not follow Vicki’s path. Where Vicki was brave and adventurous, Paula was cautious.

She attended college close to home and married right after graduation. She wanted to work abroad, but never pursued it. She wanted to someday travel to Peru, but couldn’t overcome her fears.

“I made decisions that were safe but limited me,” she said. “I avoided situations where I’d be trusting or putting my fate into other hands.”

6

Lost connection

One day in December 1987, Paula, a new mom living in Buford, went downstairs to unpack her Christmas decorations.

As she moved around a tall stack of boxes in the corner of the room, she spotted a shredded cardboard box wrapped in tape and marked, “Vicki.”

It had been years since she’d last read Vicki’s letters from Peru, penned in small, neat cursive on thin, airmail stationary.

When she opened the box she was stunned to find only dust. The letters had been destroyed by termites. She dropped her head and wept.

The letters were not only Paula’s strongest connection to Vicki’s last days, but they were also the last trace of an address for Maria Alcantara.

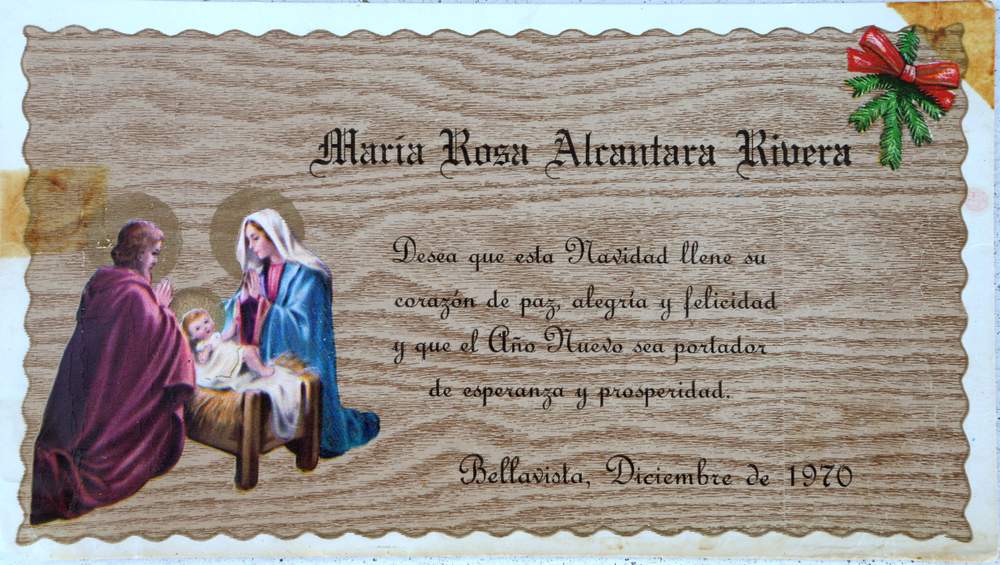

This Christmas card from Maria, the Christmas after the crash, was likely the last communication with Maria until they reconnected.

Now all she had was Maria’s name, a common one in Peru.

The emergence of the Internet in the late 1990s gave Paula new hope. She searched for Maria, but without an address or knowing her married name, it seemed impossible. Jeannie also tried but got nowhere.

In March, Paula’s mother died from a stroke. She was 79 and had long suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Paula’s grandmother died from Alzheimer’s, as well as her maternal uncle, and he was only 68.

Convinced she may also face Alzheimer’s someday, Paula worried time would run out before she could connect with Maria and learn everything there was to know about Vicki’s last days.

ABOUT THE STORY

A loyal reader of Personal Journeys, Paula Ashmore emailed us in September after making a recent breakthrough in her search to learn more about her sister Vicki’s life as an exchange student in Peru in 1970. When she met with Paula, AJC reporter Helena Oliviero was struck by the close relationship between Paula and Vicki. It was clear Paula had clung to vivid childhood memories laser-etched onto her heart. After the story was scheduled to run today, we later learned the significance of the date. The result is a bittersweet story of loss, grief and the power of shared experiences.

Suzanne Van Atten

Personal Journeys editor

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Helena Oliviero joined the AJC in 2002 as a features writer. Previously she worked for the Sun News in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Knight Ridder as a correspondent in Mexico. The leader of the pack in Personal Journeys, she’s written 15 to date. She was educated at the University of San Francisco.

Readers responded in a big way to this Personal Journey after it was published on Sunday, Nov. 15. One letter, from retired WSB anchorman John Pruitt, adds another dimension to the story.

I enjoyed reading your Personal Journeys story about Paula Ashmore and the impact she and her family suffered when her sister Vicki died in a Peruvian plane crash in 1970.

The crash and Vicki’s fate had impact on me as well. I was 28 at the time and preparing the Sunday night newscast at WSB when news of the crash came over the wires. As the wires updated the breaking news we learned many students were on board, and at one point the names of some of the students on the manifest were revealed.

As I was sorting through the information I received a call from Paula’s father. In a very calm voice he explained that his daughter had been in Peru on a student trip and he wondered if I could share any information I might have about the crash. Then he asked if I had any names of those on board. I was very reluctant to share this because nothing had been confirmed, but I did tell him the wires had released some names of those on the flight. He then paused, and, in a quiet voice, asked if Vicki Ashmore was on the list.

Vicki’s name was there, and I realized I would be the one confirming to this father that his daughter had perished. It was not a position I wanted to be in, but I didn’t feel I could deny this father’s attempt to confirm his worst fear.

“Mr. Ashmore, her name is on the list.” The calm voice on the phone broke into a sob as the line went dead. I will never forget the unspeakable grief of that moment. I always wondered about how this family dealt with this tragic loss. And as my own two daughters were born, the memory of that phone call continued to haunt me.

Paula’s story brought that night back to me, and I thank her for sharing it. I would appreciate your sharing this with her if you think she might like to know.

Sincerely,

John Pruitt

Please confirm the information below before signing in.