2

Numb long before

The first time he was born, Ulysses didn’t stand much of a chance. African-Americans in Waynesboro in the years before the civil rights movement didn’t have much path to prosperity. Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat the year before Ulysses’ birth. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would not “have a dream” for another eight years. The civil rights luminaries of 1960s Atlanta and the greater South may as well have been a million miles from Waynesboro.

Ulysses was, for all intents and purposes, orphaned as a child. He never knew his father and his mother was institutionalized with mental illness when he was young. Ulysses grew up with his maternal aunt and her family, working and living on a white man’s farm. It wasn’t slavery, but it was close enough. He picked cotton and soybeans and slept nights in a windowless two-room shack near the field where the family worked. There was no running water, no bathroom.

Struggling with an undiagnosed case of dyslexia, Ulysses dropped out of school in the seventh grade, a decision that met no resistance from his home or school governing bodies. They didn’t send truant officers for poor black kids in rural Georgia in the 1960s.

When he quit school, he was put to work on the farm with his aunt and her family, side by side each day in the field and each night shoulder to shoulder asleep in that farm shack.

“I stayed like that for a while until I got kicked out,” he said,

By the age most kids were in middle school, Ulysses had already developed a reputation for drinking too much. After yet another night out drinking and another no-show at the farm the following day, his aunt demanded he leave, so he went to live with a cousin.

“That’s when I really started really drinking and really acting stupid; fighting, drinking, stealing. I was doing a lot of that stupid stuff,” he reflected.

He eventually got a job working on a garbage truck, then he went to work for a Mennonite family farm. He regrets much about his time with them.

“They helped me in so many ways and invited me into their house, and I still treated them real bad. I was stealing their gas and things like that. I was breaking their hearts, but they never had me locked up.”

During that time, Ulysses and his then-girlfriend had a daughter together. He was 17 years old, she was just 13. They married when she found herself pregnant with their second child a year later.

“I was not a good man when I lived in Waynesboro. I didn’t grow up good. I didn’t act right. I was always drinking, and I beat my wife if she had something to say. I had another family at the same time, too, but I left both of them and all my kids for Atlanta one day.”

It was the late 1970s when Ulysses, 21 at the time, arrived in the city. Theft quickly became his full-time job.

He snatched purses, robbed houses, rifled through cars. Anything to get money and buy liquor. Nothing shut up the worry, fear and demons that plagued him like a fifth of vodka. Except maybe cocaine. High and drunk was all he lived to be.

Ulysses was numb long before he couldn’t feel his legs.

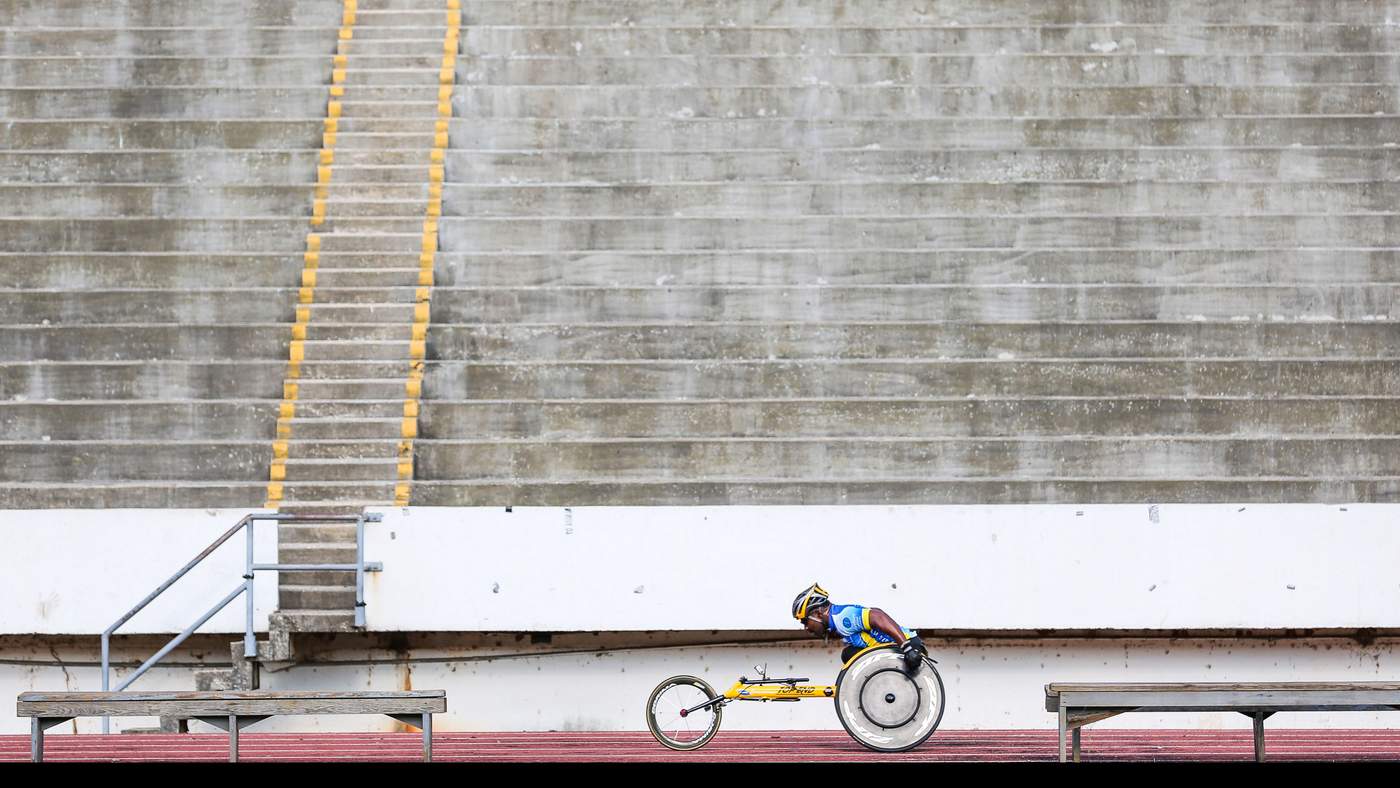

Photo: Ulysses wheels down busy streets to the Avondale High School track to train. Photo by Emily Jenkins

4

Run for your life

Ulysses was finally outrunning his demons. He joined the racing team at Shepherd Center and was winning races and gaining praise. He had hit the proverbial rock bottom and was on the path back to the top. Or at least he was, until, like many addicts, his journey took a circuitous route.

Throughout the 1990s, Ulysses started falling in and out of trouble, fueled in part by John’s death.

“When John died, it was a big loss for me. I had looked up to him for years because I think he was in my life for a moment and he was there for a reason. He didn’t have to come all the way out from Roswell three or four times each week to get me ready for the Peachtree. It’s 2016 today, and I can still remember him saying, ‘Don’t never quit on a race. If you quit you lose.’ So now I never quit.”

There was also a romantic relationship that turned sour.

“When you love someone, your mind thinks all sorts of stupid stuff,” said Ulysses. “So what I did, I took about a handful of Motrin pills and I waited to see what was going to happen.”

He’d wanted to end his own life, but then he had second thoughts.

“When I got to feeling dizzy, I got someone to call an ambulance. They kept me in some kind of hospital for four or five days.”

Whether it was a cry for help or an authentic desire to end it all, it doesn’t really matter. Ulysses was again as lost as a man can be in this world.

Which is precisely the kind of man the Rev. Victor J. Belton hoped to find when he visited the hospital where Ulysses was recovering.

Belton came to the Glenco community more than 20 years ago to lead Peace Lutheran Church, a small congregation in a poverty-stricken community south of Avondale Estates and west of East Lake where the average per capita income is lower than 95.4 percent of all American neighborhoods. It’s the kind of neighborhood where 25 percent of the homes are abandoned and unkempt. Entire shopping centers sit vacant, worn by weather and neglected in upkeep.

“I met Ulysses when he was feeling low about life,” said Belton. “It was clear he was ready for a change. Sick and tired of the mess and the noise.”

Belton quickly homed in on a gift Ulysses had never put to good use: His amazing capacity to remember. Ulysses could spout Bible verses from memory.

What Belton didn’t know was that Ulysses, who had yet to overcome his dyslexia and learn to read, had been practicing with recordings.

“I had a hunger to know the Bible,” said Ulysses. “I could not read the Bible. I would put a Bible CD in the player and follow along in the book. I still have the CDs and cassettes at home, but I now know to be starting at Genesis, or turn to the right chapter on my own.”

The church embraced Ulysses, first giving him a role as an usher and later elevating him to church elder. He began to lead others in Bible study. He started ministering to those spiritually lost or injured. All the while he still raced.

“I think I saw that God can still use me, even though I am in this wheelchair,” Ulysses said. “Not for me, for racing or anything like that. But for others.” At church I saw that God could use me for the first time when I saw people ushering at the church and I figured I could do that. They trained me how to help others.”

Belton sees it differently.

“We trained him only to show what he is. To bring naturally a spirit of hope to others through his resilient strength. He tells people that ‘I am in this chair. This chair has me. But this chair, it is not in me.’”

It would be easy to end the story of Ulysses Elijah at the finish line of the 2014 Peachtree Road Race when he won his division. But easy is not the life Ulysses has had, and there is no such thing as happily ever after. Becoming a good man cost him two legs, some jail time and his relationship with his daughter.

Ulysses, now 59, survives on a monthly disability check of less than $1,000 a month, a single shift at a CVS store and rent subsidy through the Section 8 voucher program. He says he’d like to work more but fears he’d lose his subsidies and incur IRS penalties. It all adds up to barely enough to survive.

Asked if he felt remorse for some of the things he’s done, Ulysses grew quiet.

“I do wish a few things,” he said, eyes welling. “I wish I could read better and earn a little more.”

“I wish,” he continued, “that I could save up some money — not much, maybe $300 — just to buy my baby daughter a headstone.

“And I wish I could call my other daughter and work things out. She won’t speak to me anymore, and I do wish I could make that right.”

As for the life of crimes he left behind?

“I regret that I did a lot of that. I made mistakes.” he said. “But, all that brought me to where I am, and I am glad for where I am. I don’t make the same mistakes no more. We all make mistakes, but the ones I made years ago, I know God has forgave me for that and so I don’t need to concern myself no more. This chair is the best thing that ever happened to me.”

ABOUT THE STORY

Readers often suggest people they would like to see us profile in Personal Journeys. Sometimes the story isn’t a good fit for various reasons, and sometimes we’ve already done a similar story. But sometimes their suggestions are perfect. That’s the case with this week’s story about Ulysses Elijah, which was suggested to us by Barbara Jung. It is a classic story of redemption and second chances.

Suzanne Van Atten

Personal Journeys editor

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Adam Kincaid is a freelance writer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Bitter Southerner and others. He wants a good literary agent and a verified twitter badge @adamjkincaid. He has two well-behaved dogs and one moderately behaved wife.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.