“Every valley shall be exalted.”

Tonight, on the first Sunday of Advent, the Christian calendar begins a countdown to Christmas.

There are many holiday traditions, both audible and edible, that make the season bright.

Among the most sublime of those traditions is the oratorio written two-and-a-half centuries ago by George Frideric Handel, placing the prophecy of Isaiah in a mighty choral frame.

Handel astounded his countrymen in 1742 with the power of his choral effects, and that power is undiminished today. In Handel’s setting, massed voices follow each other in waves, culminating in the titanic resolution that is the Hallelujah Chorus.

But unlike the ending, the beginning of the Christmas section of Handel’s “Messiah” is thoughtful, slow-paced, contemplative. After a mournful orchestral introduction, a solo tenor voice offers the reassuring salutation: “Comfort ye.”

Almost a lullaby, it’s the first voice you hear in most performances of the Messiah, and in Atlanta, for 40 years, that voice has come from an enduring local institution named Sam Hagan.

At St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Midtown, members of the congregation have said more than once, “It’s not Advent until I hear Sam Hagan sing.”

This year will mark the 39th time that Sam has appeared as the tenor soloist in the popular St. Luke’s Messiah sing-along, which will celebrate its 40th anniversary Nov. 29. (He missed one.) A slight, graying, soft-spoken, former biology teacher, Sam is transformed in song. His voice can float in the altissimo range like a mist above a waterfall or turn into tempered brass, with a sound that knocks down walls.

Sam, 73, has come up against many walls in his time. He was the first African-American soloist at First Presbyterian Church of Atlanta. One of the first black men on the faculty at The Westminster School. Among the first three black members of the Atlanta Choral Guild.

When this lyrical tenor sings the words of Isaiah, “ev’ry valley shall be exalted,” you can’t help but think about how they apply to the life of Sam Hagan. He grew up poor. His family of five shared one bedroom. His mother did domestic work.

But Sam’s angelic voice — and determination at school — won him a scholarship to Clark College. His grades at Clark won him a grant to study biochemistry at Emory University.

And Sunday night he stands at the front of St. Luke’s sanctuary, his voice reassuring the listener that the low will be brought up high, that the crooked will be made straight.

Every valley shall be exalted.

Photo: When Sam isn’t singing he’s working on this three-story addition to his house, which he is building single-handedly. His wife, Marti Hagan, has maintained a good humor about the slow but steady progress. Brant Sanderlin, bsanderlin@ajc.com

2

Building a palace

Compared to the apartment where he grew up, the house Sam lives in now is a palace. Sam is at that East Lake house one cool autumn morning. Across the street is the 15th green of the East Lake Golf Club. (An occasional duffer chips a ball into his garden.) In his two-acre yard, he circles the 1937 fixer-upper, showing off the changes that tripled its size since he bought it in 1974.

Here are the projects done and the projects yet to be completed sometime in the future:

Project One: Tear out the living room and start from scratch, adding built-in cabinets, a working fireplace and handsome moldings? Check.

Project Two: Add a wing for a new kitchen, with birds-eye maple cabinets on the perimeter and another working fireplace at the center? Check.

Project Three: Create a three-story addition with family room below and master suite above, and two more working fireplaces? Half a check.

The family room/master suite is three-quarters done, and currently hosts cables, hoses, ladders and a table saw.

Outside, the brick exterior is painted a different color than the rest of the house. The cedar shingles he carefully nailed into place on the roof now all need replacing.

Someone in this situation might get angry at a dilatory contractor, but there is no contractor, there is no crew. It’s Sam and his two hands.

Adjacent to the addition is a deck, over-engineered with enough concrete and rebar to withstand an atom bomb. Waist-high brick walls with ornamental caps encircle the open area, but some walls, doors and windows have yet to materialize.

“I think Sam is building the Westin Peachtree,” says his very patient wife, Marti Hagan. The two met in 1973 and married five months later. Their bond has solidified around a mutual love of music and a hunger for travel.

For now let it be said that Marti’s love for Sam generates tolerance for his single-minded insistence that he will rebuild his house, on his own, even if it takes 15 years, which it already has.

“I used to say that every time I heard Sam sing, I fell in love again,” says Marti. “It’s not about living in a tidy, sterile space. It’s about Sam pursuing one of his multiple interests.”

Photo: Sam has performed with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, The Choral Guild and the Atlanta Opera. He’s seen here with the Atlanta Opera in the role as Emperor in Puccini’s “Turandot.”

3

Lake George Opera

The two met in Lake George, N.Y., near where Marti’s parents, Reg and Juanita Ellis, lived. Her father, a civil engineer, designed the bobsled run for the 1932 Olympics in nearby Lake Placid. Marti was managing a regional opera company at the time, the Lake George Opera. Sam was booked to perform “Tosca” and “Rigoletto” with the company, and Marti, responsible for finding lodging for her out-of-town singers, was coming up empty.

Usually the traveling singers would stay with local families, but after finding out this singer was black, families turned down Marti’s request for lodging.

A week before Sam’s arrival, a desperate Marti called her parents in nearby Diamond Point. They agreed to put him up for a while. He immediately became their favorite guest.

“The morning after Sam arrived, my mother called, wanting me to come for dinner,” says Marti. “My mother was in love.”

After two failed invitations, Juanita finally got her daughter to come to dinner with the lure of pork chops and sauerkraut.

“Supper went really well,” says Marti, a chipper woman with a ready smile. After the meal she accompanied Sam to a rehearsal at a nearby Episcopal Church. He sang the first phrase from Mendelssohn’s “If With All Your Hearts,” and the organist was so stunned, she took her hands off the keys.

Marti was smitten.

While her parents were all in favor of Sam, Sam’s mother, Irma, was tentative about her only son marrying a white woman.

“She lived back in the day when there were lynchings,” Sam said. “She told me, ‘You’re getting into trouble here.’”

It wouldn’t be the first time.

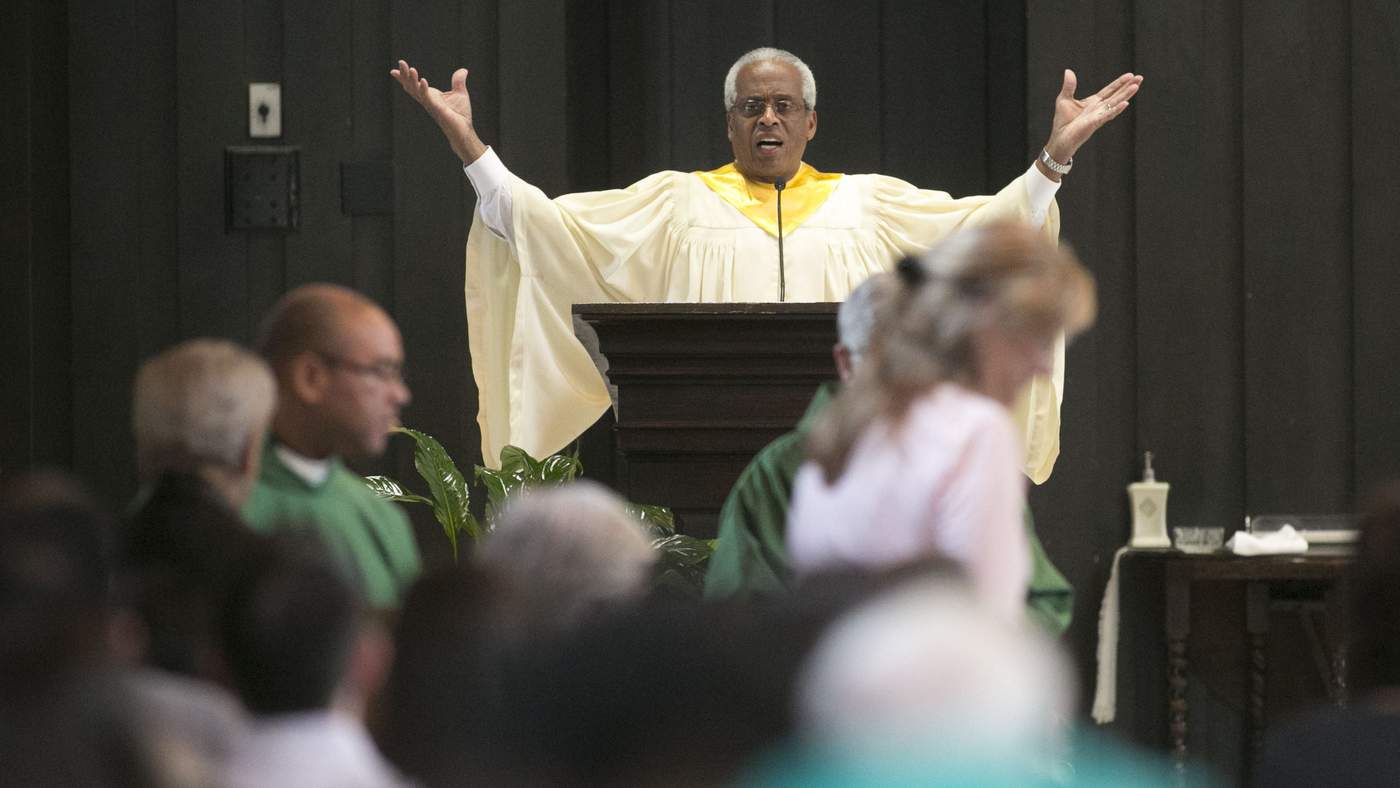

Photo 1: Sam Hagan helps lead services at St. Jude the Apostle Catholic Church in Sandy Springs. Phil Skinner, for the AJC. Photo 2: Sam and Marti Hagan are inveterate travelers. They're seen here on Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy in the eastern Canadian province of New Brunswick.

4

Singing in church

In 1970 Sam joined the staff at First Presbyterian Church of Atlanta as a tenor soloist, becoming the first black member of the choir.

“He was well accepted by the majority of people but not others,” says Paul Cadenhead, who was an elder at the church and sang baritone in the choir.

At least one family left the church.

Later, when pastor Harry Fifield performed the marriage service for Sam and Marti, more members would become irritated.

Asked how he coped with the prejudices he encountered in life, Sam paused.

“By coexisting,” he finally said.

Sam’s friend Ralph Freeman says Sam’s poise in adversarial situations is a strategic choice.

“When you exude confidence in who you are, people are reluctant to attack you,” says Freeman.

Over time, Sam was embraced by the church.

“There was an absolute love for the guy,” said Cadenhead. “He is a lovable guy.”

When music director Herb Archer retired in 1988, Sam left too. But each December for the next 15 years he would return for a Christmas concert, and the crowd was so big, it could barely squeeze into Fifield Hall.

On All Saints Day 2015, Sam drives north at 7:30 a.m. to his latest assignment, cantoring at St. Jude the Apostle Catholic Church in Sandy Springs. As cantor he stands before the congregation, leading the worshippers in hymns and responsorial psalms, raising his arms to signal musical responses.

The day’s music includes “For All the Saints” and a haunting version of “Shall We Gather at the River,” arranged by Aaron Copland.

When Sam sings, fellow choir member Jamie Morrison, 56, likes to put his glasses on.

“My favorite thing to do is watch the people that watch him,” said Morrison, “especially the older crowd. I know they’re tearing up. He just tells the story.”

Sam is in the minority at this church too. Today these differences seem immaterial. “He’s my brother,” says choir member Carol Wood. “We just had different parents.”

After three services, Sam passes through the emptying sanctuary, with its soaring ceiling, natural stone walls and primitive carved wooden crucifix. On the drive back home, he talks about the most spiritual moments of his life.

They didn’t happen inside churches.

Sam was raised a Seventh Day Adventist, and singing in church helped set him on a path to become a musician. But the church’s strictures pushed him away. When he got a gig singing the classics at an Italian restaurant, church leaders told him he couldn’t perform at a “tavern.” He decided he liked singing more than being told what to do.

Sam finds his spiritual sustenance in the wild — in a sleeping bag, lying on the ground in a Nebraska bird sanctuary near the North Platte River, waiting in the pre-dawn cold to get photos of the sand hill cranes in flight.

Or visiting Little River Falls in Alabama, snapping pictures of the rain-engorged waterfall with autumn’s changing leaves painting the backdrop in golds and reds.

Sam and Marti have been to 36 of 59 National Parks, and most of the provinces in Canada.

“When I get to see those falls, to me that’s as much of the spirit as I need,” he says, pulling onto 400 South.

Photo: Sam’s other passion is home improvement. His home is an ongoing renovation project. He has worked single-handedly on his house for 30 years, moving from one project to another. Brant Sanderlin, bsanderlin@ajc.com

5

Changing world

If it’s a different world than it was when Sam and Marti got married, the starkest change can be seen in their own neighborhood. White flight had emptied East Lake of middle class families by 1974, and the area around the historic golf course was riddled with crime. The Hagans became founding members of the neighborhood association and patiently worked to improve the area.

When developer Tom Cousins bought the East Lake Golf Club in 1993 and returned it to the glory of its Bobby Jones years, things began to change. Today the noble old houses around the golf course are being renovated, or bulldozed. Property values are up. former NFL star Warrick Dunn is a neighbor.

Sam and Marti bought their house for $25,000. That investment has improved. But attitudes have also improved. At the closing in 1974, the seller waited until all were seated in the real estate lawyer’s office before he announced, “I ain’t taking no check from no (racial slur).”

After a painful silence, the seller’s lawyer agreed to write the check and have Sam reimburse him.

Photo: At St. Jude the Apostle Catholic Church in Sandy Springs. Phil Skinner, for the AJC.

7

Ev’ry valley

Marti is only halfway joking, and though Sam can be seen climbing scaffolding, hauling lumber and tools, he’s had a few of the complaints, like sciatica, that flesh is heir to.

Still, they don’t seem to be ready to slow down much, which should come as good news to those in the St. Luke’s congregation who need to hear Sam Hagan sing the ancient prophecy before they get in the mood for the season.

That group includes music director Arlan Sunnarborg.

“As a performing musician and a leader it often is difficult for me to feel that I’m worshipping, because I have to be in this thinking-ahead, taking-charge frame of mind,” says Sunnarborg. “But in that moment when Sam begins to sing, he becomes my minister and my cup gets filled, and it’s the most beautiful thing in the world. For a moment he breathes those words to life and they find a place not just in my heart but in the hearts of many.”

Sam is still building his home at East Lake. The addition is even more “exalted” than the original house.

But he has another more elevated place to live: in the hearts of the congregations at St. Luke’s and St. Jude’s and many other places in Atlanta where people love beautiful music.

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

I first heard Sam Hagan sing at First Presbyterian Church of Atlanta. I’ve also participated in the “Messiah” sing-along at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, where he was the soloist. I’ve accompanied him to St. Jude’s, I’ve watched him at work in his impressive workshop, and I even had the honor of having Sam sit in with my band at a recent party, singing “Stormy Weather.” He is an unassuming man with a big smile who has accomplished much, but it wasn’t until that party that I came to know his remarkable background. The more we talked, the more I knew that his story was unique.

Bo Emerson

Staff writer

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Bo Emerson is an Atlanta native who joined The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1983. He has been a features writer for most of his AJC career, covering music, the Olympics and Billy Graham’s last crusade. He is also a musician and plays jazz trumpet with Style Points, The Lowlights, and other hackers. He is married to Maureen Downey, who covers education for the AJC.

EVENT PREVIEW

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church celebrates 40 years of the Messiah sing-along at 7 p.m. Nov. 29. The free event will include a chamber orchestra and professional soloists, under the direction of Joseph Young, assistant conductor of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Those who wish to sing can bring their own score or purchase one at the church. 435 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta. 404-873-7600, stlukesatlanta.org.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.