"The first time I remember something happening was right after my fourth birthday. I was wearing blue jean overalls, Mary Jane shoes and a pink shirt. He took me in a room and touched me.

"It wasn’t anything major until I was 9. I was on the bed. He was like 300 pounds. I screamed because it hurt. He choked me until I passed out. When I woke up he showed me a knife and said he would murder my whole family if I ever said anything.

"He would tell me, 'This is God’s will.' He would tell me he owned me.

"It caused me to not believe in God. I was like, I’m being abused. There can’t be a God if this is happening.

"It was wrong of me to say that about God. It wasn’t fair. God chooses His strongest warriors to fight His biggest battles."

A young woman enters a busy banquet room. All around her, loud and happy women shake the air with their laughter. Felicia Villegas sits in silence, alone with her truth.

The event is the YWCA of Northwest Georgia’s annual Tribute to Women of Achievement luncheon. The Cobb County organization runs an emergency shelter and offers counseling and other services to victims of domestic violence. The February luncheon features a panel of past Tribute honorees.

Marietta High School Principal (and 1983 graduate) Leigh Colburn, a civic leader beloved by students and community members alike, is on the panel and has invited Felicia to share her story. It’s OK if we get there and you decide you don’t want to talk, Colburn has told her.

"I’m going to look at you," she tells her former student on the drive over. "Give me a thumbs up or thumbs down."

"I would think about my homework to try to take myself away from what was happening. If I couldn’t, if it was too painful, I would just think, it’s almost over.

"When I was 7 or 8 I remember watching ‘Nancy Grace.’ Somebody was arrested for doing something with a small child. I realized, that’s what’s happening to me.

"I asked him about it. He grabbed the gun and said, ‘If you ever tell anybody I will kill you.’

"Even though I had never talked about it to anyone before, I knew I could never talk about it now. My life was at stake.

"I kind of accepted this was my fate. My job in life was to please a man who was going to hurt me."

The panel discussion starts and Felicia gives a thumbs-up.

"What impact has your involvement with the YWCA had on you?" the moderator asks. Colburn says Felicia will answer in her place and hands over the microphone.

In seconds, the room is hushed. Tears stream down cheeks. Everyone is still for a heartbeat, then stands to applaud.

Felicia is a little overwhelmed.

Afterward, people line up to meet her. When the crowd thins I introduce myself and we make plans to meet. It’s an act of bravery that I don’t fully appreciate at the moment.

Over the next several months she will more fully reveal the dark dungeon that was her childhood. I will comb through court documents that sting my eyes and bruise my heart. I will come to believe that God sends angels to walk among us. Some work in homeless shelters. Some work in high schools. Some wear badges and blue uniforms.

At 20, Felicia has spent much of her life at the intersection of good and evil.

"I’m not a victim," she says. "I’m a survivor."

8

'I'm a fighter'

Felicia never wants to see her abuser again. She considered writing him a letter once, but didn't.

"Sometimes I want to tell him how he hurt me," she said.

Instead, she is focused on her future. Her youngest child, an adorable son, is toddling around and learning to talk. Her bright and outgoing daughter loves horses and twirling like a ballerina. She and Felicia practice penmanship and vocabulary by writing stories together.

"I feel like my life is finally settling down," Felicia said. "I'm a fighter. I know I'm worth fighting for."

She has worked as a telemarketer and house cleaner and in fast-food. She was in between jobs when I visited the other day to deliver a meal for her family. The central air had gone out and they couldn't afford the repair. A little air conditioning unit chugged away in one window, landing limp punches against the heat. If you stood still and in the right place, there was a little relief. Take one step away and the heat was all around you, a giant hand ready to re-tighten its grip.

But Felicia seemed at peace.

"If I hadn't gone through what I went through I wouldn't be who I am," she said. "It made me stronger."

We get together every few weeks and we are working on a book about her life. She hopes it will help other young victims who feel afraid and helpless.

"When you finally have a voice, you might as well use it," she said. "I want to be that voice for others."

The book doesn't have a title yet. She's going to take some time to decide.

"I don't know," she said. "My story's not over."

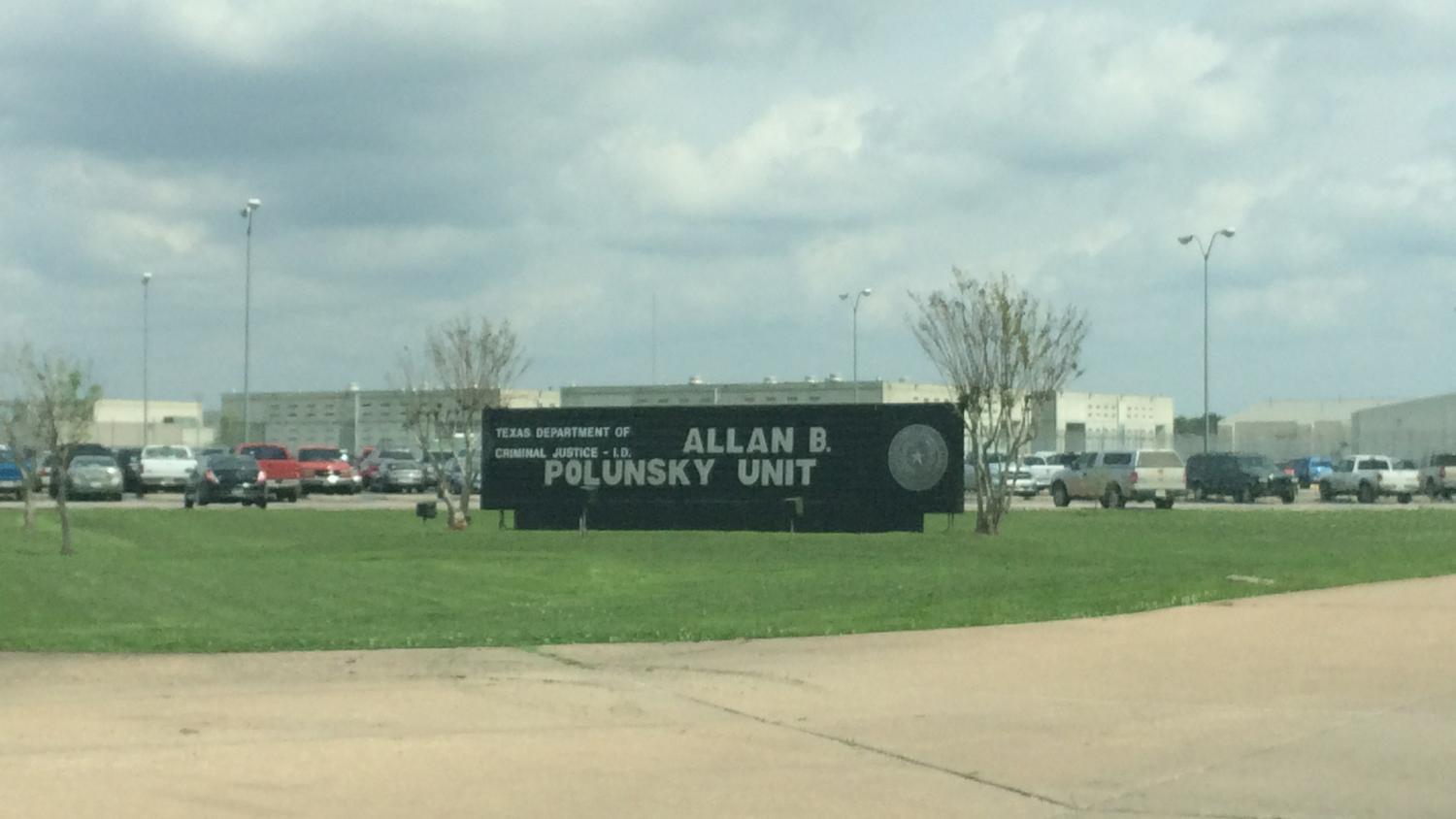

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

I have served on the board of the YWCA of Northwest Georgia and remain a supporter. I was on the YWCA panel with then-Marietta High School principal Leigh Colburn (now director of the new Graduate Marietta Success Center) the day she introduced Felicia Villegas at the Salute to Women of Achievement luncheon. I’ve spent hours with Felicia and her family over the past five months and traveled to Texas to interview her abuser in prison and Austin Police Sgt. Carl Satterlee, who helped put him there. I’ve never met anyone more inspiring and courageous as Felicia. It has been my greatest honor to know her and help her share her story. The Y’s 24-hour crisis line is 770-427-3390.

Jennifer Brett

Staff writer

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Jennifer Brett has been a reporter at the AJC since 1998, covering politics, education, business and the 2008 Beijing Olympics before moving to the celebrity/entertainment beat. A North Carolina native and graduate of the University of North Carolina, she is a member of the Junior League of Cobb-Marietta, Cobb Landmarks and Historical Society and Marietta First United Methodist Church. She and her husband, Charles Gay, live in historic Marietta.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Brant Sanderlin has more than 20 years’ experience as a photojournalist, including 15 at the AJC. He shoots a variety of assignments, including front-line action during the Iraq war, sporting events, breaking news and human interest stories. He grew up on the family farm in eastern North Carolina.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.