Returning for lunch, I counted up the customers: by my amateur estimation, the dining room looked to be filled with about a quarter pile of people or so, all silently munching through plates of barbecue. Another dozen or so individuals stood clutching Styrofoam plates, quietly queued up, like pilgrims waiting to touch a holy shrine, before a buffet-style steam table. I paid for a plate, took my place behind an elderly woman whose royal blue blouse neatly matched her bouffant, and inched my way up the line. We waited as preceding customers swarmed the first station of the buffet table: barbecue.

Heat lamps threw a string of pale-orange halos upon a four-foot long chafing dish that contained an unholy mess of barbecue pork. With the meat chunked and pulled, and fried pork skins scattered about, it looked as if a pig had exploded. I rummaged through the meat with a pair of kitchen tongs, piling my plate with some dark, a couple pinches of white, and a triangular jib of crisped skin. I moved on down the line feeling more than a bit bewildered. A barbecue buffet? Just as I was beginning to find my barbecue bearings, I felt I’d crash-landed, a man fallen to earth, Piggy Stardust.

The table’s far end opened up on to the usual blanket of southern sides: collards and cabbage and limas, green beans with boiled potatoes, macaroni swamped in neon-yellow cheese, potato salad, fried okra, squarish lumps of yeast rolls, and mayonnaise-whipped coleslaw. There was fried chicken, banana pudding, and an untouched salad bar. In the thick of the sides was a deep-troughed warming pan brimming and burbling with a brown-gravied stew called barbecue hash, or simply hash, in this part of the state. Though from the way customers ladled thick globs of the stuff onto their plates, it looked like an embarrassing kissing cousin to chili that had fortunately been consigned to oblivion long ago. This mysterious meat soup evidently played the sidekick role to barbecue here. Following the lead of my blue-haired guide, I poured a dipperful over a bed of white rice. I smiled at her with a knowing nod, to tell her that I knew just what I was doing.

Following Big Joe’s death, the arrival of a new Bessinger-owned barbecue shop became a seemingly annual event throughout South Carolina. Each opening, and inevitable closing, portended another soap-operatic schism between brothers. Just before his father’s passing, Melvin opened Eat at Joe’s across town from Joe’s Grill. In 1953, Maurice returned to South Carolina and with another older brother, Joe David “J. D.” Bessinger, opened Piggie Park in Charleston.

Within five months, they split; the elder brother kept the restaurant, bringing in brother Woodrow, while Maurice decamped to Winston-Salem to open another, now nonaffiliated, Piggie Park. North Carolina didn’t take to barbecue from the other side of the state line, so Maurice hightailed it back to South Carolina, relocating to Columbia, to launch the second coming of Piggie Park.

Soon after, Melvin, together with another brother, Thomas, opened his own drive-in barbecue restaurant to compete with J. D.’s original Charleston location. Naturally, they named their operation Piggie Park. Back in Columbia, Maurice had hit the barbecue jackpot, opening six additional Piggie Parks across the state capital by 1963.

Finally, at some nebulous point in time, Robert, the Zeppo Marx of the Bessinger brothers, operated two barbecue storefronts in North Charleston. Thankfully, these locations were never named Piggie Park.

If you’re confused, so am I. The point is, Bessinger barbecue, in all its familial iterations, spread Big Joe’s mustard sauce across the map of South Carolina like an invading virus, with each brother serving his own version. Nowadays, this mustard-sopped sauce is a nationally known condiment. The Golden Secret produces gold like Joe Bessinger’s cow — poor Betsy — once produced milk. In fact, if he were alive today, Big Joe could trade back his original recipe for millions upon millions of dairy cattle. But once money could be made elsewhere, the Bessinger’s hometown was forgotten. The quiet closings of Joe’s Grill and Eat at Joe’s yanked little Holly Hill from the limelight, reducing the town to a mere footnote in barbecue’s history.

Though Melvin Bessinger registered the copyrighted use of the Golden Secret name, it was his scrappy younger brother Maurice who became the king of South Carolina’s mustard barbecue. Trotting into the 21st century, his empire had expanded in directions no other Bessinger dare stride. He had built his very own Willy Wonka–styled barbecue factory, pumping out bottles of his Carolina Gold brand sauce for grocery store shelves stretching from New York City to Tampa Bay.

ABOUT THE STORY

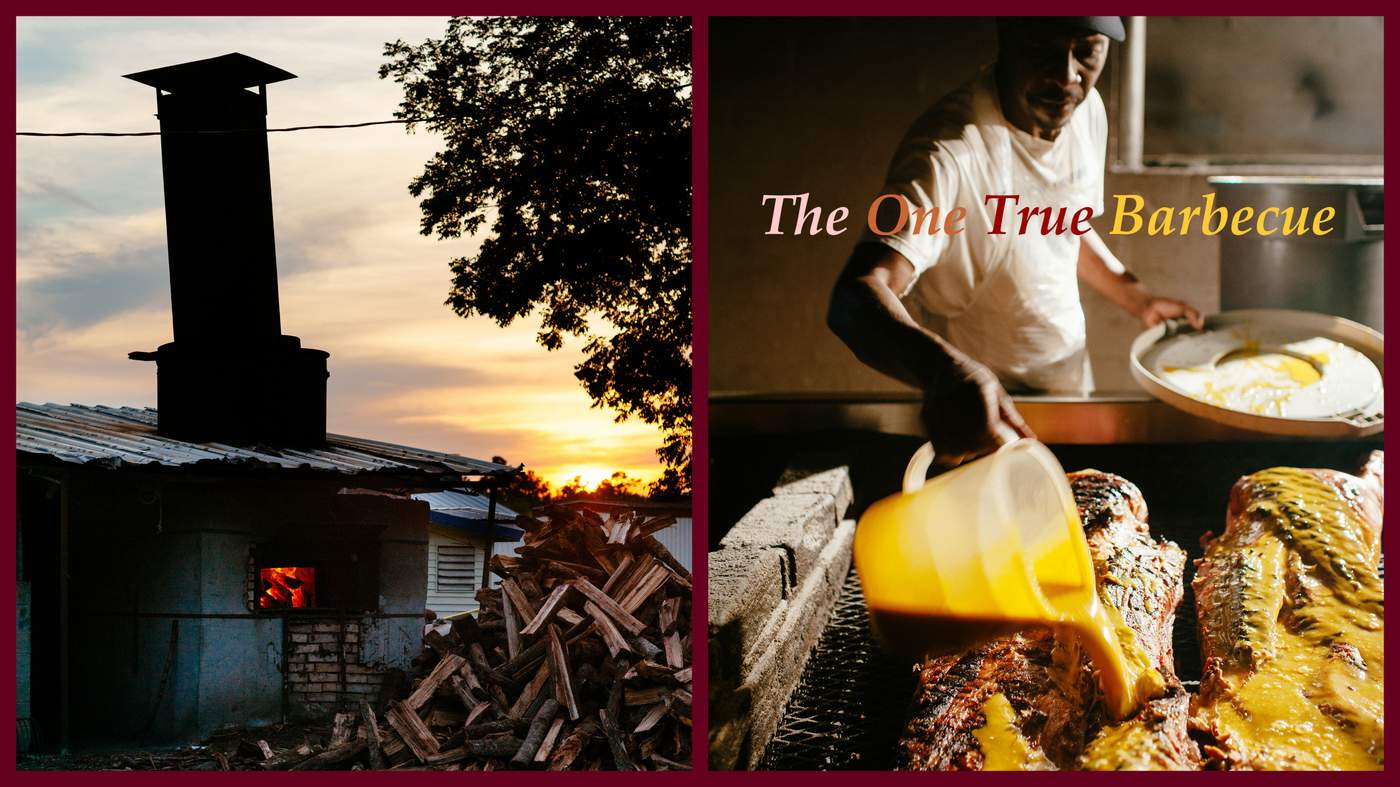

Nothing says Independence Day like American flags, fireworks and hot dogs. But in the South, it just isn’t the Fourth of July without barbecue. Our region is famous for its pit-cooked pork, and its many variations delineate the South’s culinary differences, often along state borders. But not in South Carolina. Our neighbor to the east boasts several iterations of the dish, including one made with a unique gold-colored, mustard-based sauce. In “The One True Barbecue,” author Rien Fertel travels the country to unearth stories about the makers of our beloved ‘cue. In this excerpt, he explores some of the not-so-savory sides of South Carolina’s barbecue lore.

Suzanne Van Atten

Personal Journeys editor

personaljourneys@ajc.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rien Fertel is a Louisiana-born-and-based writer, historian and teacher who grew up washing dishes and busing tables in his family’s chain of restaurants. While earning a PhD in history, he spent four years on the road documenting barbecue for the Southern Foodways Alliance. His work has appeared in dozens of print and online publications. He lives and teaches in New Orleans.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.